Our Goals

Raise awareness

Offer support

Source Funding for research

What is

Charles Bonnet Syndrome (CBS)?

Vivid, Silent, Visual Hallucinations caused by loss of sight.

It is not a mental health condition

Charles Bonnet Syndrome (CBS) develops in a child or adult who has a variable amount of sight loss. It causes vivid, silent, visual hallucinations which range from disturbing to terrifying. No other sense is involved. It is not a mental health condition, but caused entirely by loss of sight.

The eye acts as a camera and the brain interprets what is being seen but, as sight is lost, the brain is left with nothing to interpret. Instead of quietening down, it fires up and creates its own images.

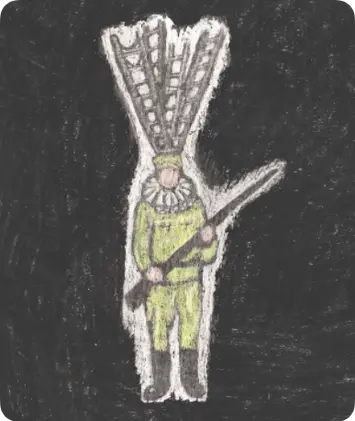

The images can be simple ones, like coloured blobs, musical notes or geometrical patterns, to more complex hallucinations of people, animals, plants,insects, rodents, reptiles, buildings, vehicles, fire, water or whole scenes. If images of people are seen, they are often in costume of some sort, with hats or headdresses – e.g. Edwardian, Medieval, Middle Eastern or Military.

People are usually aware that the hallucinations are not real because the images are sharp and clear, as opposed to the person’s vision. Some people have recurring hallucinations while others see different images each time. The images can occur frequently or occasionally and can be made worse by stress, isolation, fever, certain medications and other conditions.

Everyone’s experience of CBS is different. The hallucinations may grow less frequent in time or may remain for many years.

Not everyone with sight loss develops CBS but, for those who do, the condition can be distressing and debilitating – not least because it may be mis-diagnosed as a mental health condition.

Far too many people who develop CBS have received no warning about the condition and, consequently, are frightened to confide in anyone.

Who was Esme?

Esme was Judith Potts’ mother. Having trained as a children’s nurse at Paddington Green Children’s Hospital, Esme’s long working life was spent looking after people – from new born babies to school-children; as a welfare officer to nurses; and, in her seventies, stepping in to allow families a break from the responsibility of caring for an elderly parent.

Resourceful and creative – her sewing machine always at the ready – she remained sprightly and lived an independent life, completing correctly the Telegraph cryptic crossword every day. Glaucoma had been diagnosed when she was in her eighties, but it was when Charles Bonnet Syndrome struck that her life changed irretrievably.

Like too many others, she said nothing until she could bear it no longer. Her quality of life was being challenged and her fear of mental illness was paramount. By the time she finally confided in Judith about her ‘visions’ – faceless people on her sofa, a tear-stained, Edwardian street child, a hideous gargoyle-like creature and sometimes the whole room morphed into an alien place – the hallucinations had reached constant and terrifying proportions. They remained with her for the rest of her life.

There was no support available. Neither her optometrist nor GP had heard of CBS and her ophthalmologist – who clearly did know the condition – refused to discuss it and allowed her uninvited images to torment Esme’s final years.It seemed entirely fitting to name the CBS charity after her.

Illustrations from people who live with CBS

Who was Charles Bonnet?

Charles Bonnet (1720-1792) was a lawyer by profession but also an eminent naturalist and philosopher. He lived in Geneva, Switzerland. In 1760 he documented the visual hallucinations being experienced by his 87-year- old grandfather, Charles Lullin, who was nearly blind from cataracts in both eyes. Bonnet knew that Lullin was ‘of sound mind’, so recognised that the hallucinations must be caused by loss of sight. The syndrome was named after Bonnet in 1937 by George de Mosier, another native of Geneva.

“Charles Bonnet Syndrome is surprisingly common and may affect up to 50% of people with visual loss. It can also be terrifying and has a huge impact on quality of life. There is no cure and the current treatment options are very limited. I am happy to support Esme’s Umbrella in its work to raise awareness of this debilitating condition.”

Dr Sarah Jarvis MBE